5 Core Training Myths After Spinal Fusion

Uncover the truth about core training after spinal fusion as we debunk common myths and reveal safe, effective rehab strategies for a stronger, healthier spine.

Key Takeaways

- “Core training is dangerous after spinal fusion.”

In reality, core training—when clinically supervised and properly individualized—is generally safe and can support recovery after spinal fusion. - “Core training is ineffective after spinal fusion.”

On the contrary, personalized core training often improves function, balance, and spinal support, provided that exercises and timing are adapted to the patient’s needs. - “Core training will cause further damage to the spine after fusion.”

Safe, guided core exercises are designed to support and stabilize the spine, not harm it, and can be an important part of a well-structured rehabilitation program. - “Core training is unnecessary after spinal fusion.”

Neglecting core training may lead to weakness and imbalance; gradual, supervised strengthening of the core is important for maintaining spinal health and aiding recovery in the long term. - “Core training will not improve spinal stability after fusion.”

In fact, progressive, well-designed core exercises can enhance spinal stability, improve overall function, and lower the risk of complications for most post-fusion patients.

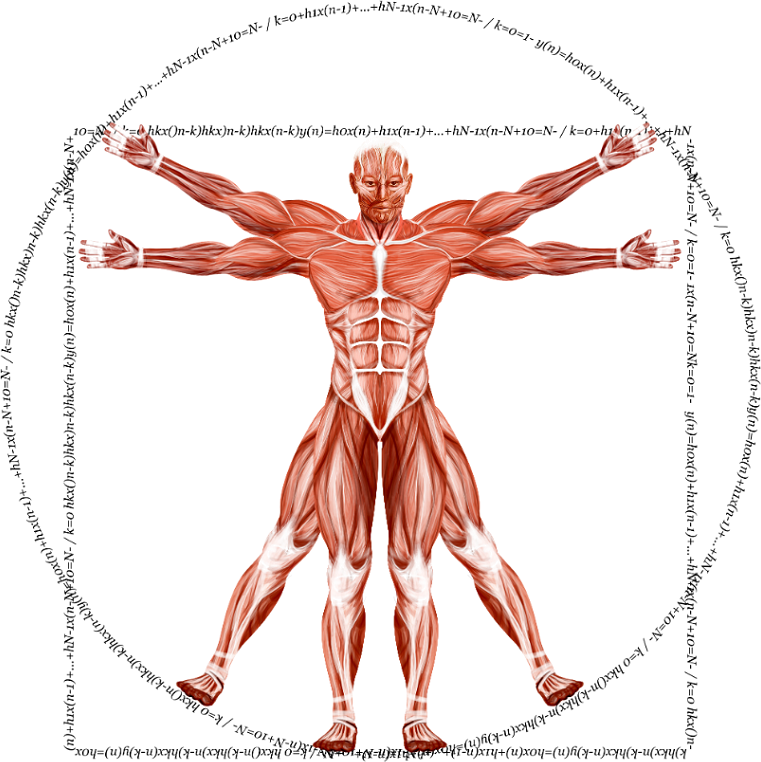

Throughout our lives, the health and stability of the spine profoundly influence our comfort, mobility, and independence. When debilitating back problems arise, modern medicine often turns to spinal fusion—a surgical technique that, while effective, brings many questions and uncertainties for those facing it. Among the most common concerns is how to safely and effectively regain physical strength, especially when it comes to the body’s core.

Core training after spinal fusion often sparks debate and is surrounded by myths that can lead to unnecessary fear or hesitation. Yet, understanding the role of the core in supporting the spine, along with the realities of post-surgical rehabilitation, is essential for a successful recovery. In the following article, readers will find clarity on common misconceptions regarding core exercises after spinal fusion, learn why and how core strength matters, and discover practical strategies for building a stronger, more resilient body as part of the healing journey.

Myth 1: “Core training is dangerous after spinal fusion.”

Misconceptions abound regarding physical activity and rehabilitation after fusion, particularly in relation to core exercises. The first myth suggests core training is inherently dangerous after spinal fusion. This belief stems from understandable fears: patients and even some practitioners worry that engaging core muscles could jeopardize the healing surgical site or cause complications such as re-injury or failure of the fusion. This concern is often rooted in misunderstandings about the phases of healing and the biomechanical role of the core in supporting the spine.

In reality, when performed correctly and under professional supervision, core training can be a safe component of rehabilitation after spinal fusion. The key to safely incorporating core training lies in understanding the body’s natural healing process. After spinal fusion, the body needs time to create a stable, solid union between the fused vertebrae. While bone healing is mainly determined by biological factors—such as the success of surgery, the patient’s age, and general health—the surrounding muscles can be gradually strengthened in ways that support improved function and stability. Therefore, “building strength” in the core does not accelerate the fusion itself, but helps regain function, provide enhanced postural support, and manage discomfort.

Physical therapists routinely emphasize that core training after spinal fusion should be approached with caution, but not completely avoided. Supervision is crucial: low-impact exercises that focus on stability and control, such as gentle abdominal bracing or supported movements, are commonly prescribed to help patients restore movement safely and effectively. By working closely with a healthcare professional, individuals can enhance their core strength in a way that supports their recovery, without compromising the results of surgery.

Myth 2: “Core training is ineffective after spinal fusion.”

A second myth is the notion that core training, if effective at all, must remain unchanged following spinal fusion. Some assume that once two or more vertebrae are fused, the need for core strength is minimal, or that the exercises prescribed before surgery don’t need any adjustment. This perspective fails to recognize the individualized nature of spinal rehabilitation.

In fact, research and contemporary guidelines underscore the importance of tailoring core training routines after fusion. A person’s fusion level, surgical approach, general fitness, and unique functional goals must all be considered. Post-fusion, certain exercises—especially those involving high-impact, high-torque, or excessive twisting and bending—are not recommended early on. Instead, initial rehabilitation should focus on low-load stability work, using movements that gently activate the deep abdominal muscles and trunk stabilizers, while avoiding excessive spinal flexion or rotation, and progressing only as healing and strength allow.

Numerous studies and expert consensus reports from 2025 conclude that therapeutic exercise, including individualized core strengthening, should be part of the structured rehabilitation phase after lumbar and cervical fusion. Physical therapists, certified trainers, and physicians are best equipped to guide adjustments and progression of exercises over time, based on healing milestones and patient feedback. This tailored approach ensures the core is strengthened safely, accommodating any anatomical or biomechanical changes resulting from the fusion.

Myth 3: “Core training will cause further damage to the spine after fusion.”

Another myth is that core training might actually lead to further damage post-fusion. Some patients remain wary, hesitant to move for fear of injuring the surgical site or “undoing” the work performed during the operation. In reality, while caution is absolutely necessary and overexertion should be avoided, professional evidence supports the conclusion that moderate, staged core exercise can support the recovery process after fusion. By focusing on the safe activation of core muscles, patients improve trunk stability, balance, and functional movement.

Exercises such as pelvic tilts, modified planks, and gentle abdominal contractions are commonly used early in a recovery program. These movements help strengthen the muscles that support and stabilize the spine, without placing undue stress on the healing segments. The key is graduated exposure and correct form; properly performed movements progressively load the supporting muscles, encouraging better posture, body mechanics, and confidence in movement.

It is important to clarify, however, that core exercises do not directly influence the “fusion” of bones—this is a healing process that depends on biological integration and immobilization of the operated segments. What core strengthening achieves is an improved ability to move and function safely, reducing the risk of secondary complications or the development of pain due to compensatory muscle habits or poor mechanics elsewhere in the body.

Myth 4: “Core training is unnecessary after spinal fusion.”

A persistent misconception holds that, following fusion, the spine no longer needs the support of well-trained muscles, since it is now “fixed” and stabilized by hardware and bone growth. This is an oversimplification that can, if internalized, lead patients to neglect crucial aspects of their recovery.

While spinal fusion indeed creates structural stability by eliminating abnormal vertebral movement, it does not guarantee the automatic function or strength of all surrounding muscles. On the contrary, muscles and soft tissues may weaken from the period of rest and immobilization required immediately after surgery. If the core and related muscle groups are neglected, imbalances and weakness may develop, possibly leading to altered biomechanics, overuse injuries, or chronic discomfort. Proper core training encourages improved posture, more efficient movement, and helps patients regain the confidence and ability to return to important daily activities.

Structured exercise programs have been shown to improve physical satisfaction and functional outcomes for many patients after spinal fusion, although individual results depend on various factors including adherence, the site and extent of fusion, and underlying health. In summary, while not every patient requires the same exercise progressions, targeted rehabilitation—including an appropriate focus on core strength—is vital for most individuals to restore strength, maintain quality of life, and foster long-term spinal health.

Myth 5: “Core training will not improve spinal stability after fusion.”

There remains some skepticism among patients and at times even clinicians about the value of core training following fusion. Some fear these exercises might do little to enhance stability or, on the contrary, may be irrelevant to recovery, thus believing their efforts are wasted. However, research and clinical observation support the value of personalized, supervised core strengthening in post-fusion rehabilitation.

When tailored to the individual, correctly dosed, and performed with proper technique, core training helps maintain and improve spinal stability. Deep core muscles such as the transversus abdominis and multifidus play a particularly important role in providing dynamic stabilization during movement. By improving muscle coordination and trunk strength, such training facilitates better control, functional movement, and a reduced risk of falls or compensatory injury. High-quality studies, peer-reviewed research, and consensus guidelines increasingly recognize the value of including staged core activities in the rehabilitation process, further reinforcing the point that such efforts can and do improve functional outcomes for many individuals after fusion.

It’s important, though, not to present this as a universal guarantee: while core training is often beneficial, each person’s program must be individualized and advances made in consultation with a knowledgeable clinician. Some patients with complex surgeries or medical conditions may require modifications, or periods of rest followed by gentle reactivation.

The truth about core training after spinal fusion

Understanding the real value and safety of core training post-fusion means recognizing both its potential benefits and the importance of individualized rehabilitation. Core training, when performed correctly, is supported by guidelines and clinical experience as a beneficial adjunct to recovery, improving function, mobility, posture, and overall quality of life. At the same time, it is not the sole determinant of success—adherence to medical advice, patience, and the timing of exercise introduction are equally critical. The fusion of bone itself occurs independently of muscle training, but a strong, coordinated core can greatly assist the body in adapting to postoperative changes and demands.

Engaging in core exercises within a structured rehabilitation program can also provide psychological benefits, such as feelings of empowerment, agency, and a greater sense of control over the recovery process. By working with physical therapists and other professionals, patients can develop a deeper understanding of safe body movement, ultimately boosting their confidence and enhancing participation in daily activities.

Tips for safe and effective core training after spinal fusion

To ensure safe and effective core training after spinal fusion surgery, several important guidelines emerge from experts and relevant literature. First and foremost, every patient should consult with their healthcare provider or physical therapist before starting or resuming exercise. These professionals can assess healing, tailor exercise prescriptions, and provide important education about posture, technique, and progression. Individual factors—such as age, the extent and location of surgery, general health, and the presence of other medical issues—influence the pace and nature of rehabilitation.

Starting with gentle, stability-focused exercises is essential for most patients. Movements such as pelvic tilts, seated marches, or modified bridges are typically favored early, as they mildly activate core musculature while minimizing strain on the healing spine. As strength improves, exercises may be made progressively more challenging, introducing balance components, resistance, or integration with whole-body movements.

However, it is crucial to maintain proper form: avoiding excessive arching or rounding of the back, not holding the breath, and progressing intensity only at the pace directed by a professional. Breathing techniques—such as exhaling during exertion—are helpful for maintaining intra-abdominal pressure and supporting spine stability. High-impact, high-velocity, or rotational movements should be postponed until later stages, if reintroduced at all.

Variety should be built into any core training routine, targeting different muscle groups and movements. Activities like yoga or Pilates may provide flexibility, balance, and core strengthening benefits, but must be adapted to each patient and guided by a knowledgeable instructor, particularly in the early or intermediate phase of recovery. Certain poses or exercises—such as deep twists, back bends, or unsupported lumbar flexion—should be avoided or modified to prevent excess spinal stress. When in doubt, professional assessment and guidance are best.

Finally, patience is of great importance. Progress after spinal fusion is gradual. There should be no rush to resume high-level activities, and most improvements are best measured over weeks or months, not days. Celebrating small advancements, maintaining open communication with a clinical team, and setting realistic expectations all pave the way for a better, more satisfying outcome.

Restoring Strength, Confidence, and Hope After Spinal Fusion

Navigating recovery after spinal fusion isn’t just about physical healing—it’s about rebuilding confidence in your own body. Many people face nagging doubts: Will I ever move freely again? Is it safe to train my core? These concerns can feel overwhelming, especially when conflicting advice and persistent myths muddy the waters.

Recovering from spinal surgery is a bit like tending a delicate garden. With patience, the right guidance, and consistency, your body can flourish again—often more resilient than you might expect. The hidden benefit is that, beyond stability, thoughtful core training can boost your energy, balance, and sense of independence, gradually dissolving the fear that often shadows rehabilitation.

Remember, one of the biggest misconceptions is that protecting your back means doing less. In reality, safe, progressive movement is your best friend—helping restore strength, reduce pain, and give you back your routine on your own terms.

Ready for a smoother recovery journey? Consider trying the Dr. Muscle app, which automates everything discussed in this article and more, letting you focus on your progress with less guesswork. Try it free.

FAQ

What is spinal fusion?

Spinal fusion is a surgical procedure used to permanently join two or more vertebrae in the spine. It is usually employed to treat painful spine motion stemming from conditions such as instability, deformities, or fractures. The operation involves placement of bone grafts and, frequently, additional hardware such as rods and screws to secure the vertebrae until bone healing completes the fusion process.

What are the common myths about core training after spinal fusion?

Common myths include the belief that core training is unsafe and should be avoided, that exercises cannot strengthen the core after fusion, that the core no longer needs to be addressed, and that only total rest supports successful healing. These views are out of step with current rehabilitation principles.

Are core exercises harmful after spinal fusion?

When prescribed and supervised by a healthcare professional, core exercises are generally safe after spinal fusion. Movements should initially be low-impact and targeted for stabilization; risky activities or excessive loads are avoided until the surgeon and therapist confirm adequate healing.

Can the core muscles be strengthened after spinal fusion?

Yes. With proper progression, core musculature can be safely strengthened after spinal fusion. Improvement in functional strength takes time and requires dedication to a professional program tailored to the patient’s level of recovery.

Should all core exercises be avoided after spinal fusion?

No. While some exercises—involving strong twisting, bending, or loading—are not recommended immediately post-op, most patients benefit from a program that includes safe, progressively challenging core-strengthening activities.

Is core training unnecessary after spinal fusion?

No. Strengthening the core muscles is important for optimal recovery, function, and spinal health after fusion. Core training assists in regaining stability, maintaining good posture, and reducing risk of future complications but should always be adapted, supervised, and performed according to professional guidance.